If you like the essay, then you'll definitely want to take a look at Luc Steels's The Talking Heads Experiment: Origins of Words and Meanings. It's published as an open-access book by Language Science Press, so go grab the free download!

Abstract

The essay analyzes why Noam Chomsky’s notion of language (both its essence — language as a set of grammatical sentences — and genesis) leads neither to interesting discoveries nor even to useful questions from the point of view of linguistics as a science. A much more fruitful approach to language is to view it as a complex, dynamic, distributed system with emergent properties stemming from its functions, as advocated e.g. by Luc Steels. The argument will be developed against the backdrop of the evolution of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s thought, from the Tractatus to the concept of language games, i.e. from an approach to language based on thorough formal analysis but also misconceptions about its functions, to a much keener though less formal grasp of its praxis and purpose.

Introduction

At least since Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, it has been a fairly commonplace notion that working within the confines of a particular scientific paradigm conditions to a certain extent the questions one is likely to ask and therefore also the answers that ensue. This effectively limits the range of possible discoveries, because some are not answers to meaningful questions within a given framework while other observations still are taken as given axioms, which means they cannot be the target of further scientific investigation.

In contemporary linguistics, one very prominent such paradigm is that of generative grammar, single-handedly established in 1957 by Noam Chomsky in his seminal work Syntactic Structures. While serious criticism has been leveled over time against this initial exposition as well as Chomsky’s subsequent elaborations on it (see Pullum 2011; Sampson 2015; and Sampson 2005 for a book-length treatment), the book undeniably attracted significant numbers of brilliant young minds under the wings of its research program, which went from aspiring challenger in the domain of linguistics to established heavyweight in a comparatively short period of time (the transition had been achieved by the mid-1970s at the latest). In the process, it co-opted or spawned various other sub-fields of linguistics, and even rebranded itself, such that Cartesian linguistics, cognitive linguistics and most recently biolinguistics are all labels which suggest a strong generativist presence.

One serious competitor to the Chomskyan account of language that has emerged over the years is the field of evolutionary linguistics. It might seem strange at first glance why biolinguistics and evolutionary linguistics should be at odds. As their names indicate, they both aspire to a close relationship with biology, which seems to indicate their research agendas and outlooks should largely overlap. Yet their fundamental assumptions about what constitutes language are so irreconcilable that they might as well be considered to deal with different objects of study. Of the two, it is evolutionary linguistics which leads to questions and investigations which can be conceived of as scientific (in the Popperian sense of involving falsifiable hypotheses instead of being merely speculative), consequently yielding the most useful insights – in the fairly pedestrian sense that these can be intersubjectively replicated without resorting to an argument from authority, which makes them a better foundation to build upon, because the superadded structures are less likely to crumble should said authority ever change their mind, as Chomsky has done several times already.

Wittgenstein on language: From logical calculus to language games

Let us now take a short détour through the development of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s thoughts on language, so that we may couch our later discussion of the differences between generative grammar / biolinguistics and evolutionary linguistics in terms of a contrast that is perhaps more familiar. The imagery in the title of the present essay was borrowed from Eric S. Raymond’s book The Cathedral & the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary (Raymond 1999). In it, Raymond describes two models of collaborative software development, one of them very rigid, restrictive and hostile to newcomers (the “cathedral”), the other overwhelmingly inclusive, open to outside contributions and organic change, an effervescent hive of activity (the “bazaar”), whose unexpected but empirically demonstrable virtues he has come to embrace.

This architectural metaphor also happens to be very apt when characterizing Wittgenstein’s view of language in the two major stages of his thought, as represented by his two books Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus and Philosophical Investigations. In the Tractatus, Wittgenstein has a “preconceived idea of language as an exact calculus operated according to precise rules” (McGinn 2006, 12) and formalizing this system of rules leads him to the following dogmatic conclusion: “what can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence” (Wittgenstein 2001, 3). The deontic force of the final injunction should be taken with a grain of salt; it could perhaps be rephrased in the following less epigraph-worthy manner: there is a sharp logical boundary to be drawn between meaningful and nonsensical propositions, and the purpose of language is to construct meaningful ones, therefore it is futile (rather than strictly forbidden) to engage in nonsensical ones.

There have been attempts to read the Tractatus in an ironic mode, as a consciously doomed, self-defeating attempt to circumscribe the limits to the expression of thought, which prefigures the much more subtle attitude towards language that Wittgenstein later exhibits in the Philosophical Investigations (see McGinn 2006, 5–6 and elsewhere for an overview of this so-called “resolute” reading). In my opinion, such a stance exhibits a blatant, possibly wilful disregard of his almost penitent tone in the preface to Philosophical Investigations: “I could not but recognize grave mistakes in what I set out in that first book” (Wittgenstein 2009, 4e).

Where does Wittgenstein think he went wrong then? Arguably, the most serious misconception was conferring a privileged ontological status to language, seeing it as “the unique correlate, picture, of the world” (Wittgenstein 2009, 49e), whereas in fact, these referential properties are highly dependent on communicative context. It signifies only insofar as it has an effect on the addressee (another human being, or even myself) which to all practical intents and purposes the speaker can identify as somehow related to what she was trying to achieve with her utterance in the first place. But there is little meaning, in any practical sense, outside these highly particular, localized (in both physical and cultural space and time), embodied, grounded interactions. Wittgenstein calls these interactions “language-games” to “emphasize the fact that the speaking of language is part of an activity, or of a form of life” (Wittgenstein 2009, 15e, original emphasis). Of course, the notion of game still involves some kind of rules, but by focusing on the activity rather than its regulations, it is much easier to account for “the case where we play, and make up the rules as we go along […] and even where we alter them – as we go along” (Wittgenstein 2009, 44e).

This is not to say that we cannot construct abstractions, although Wittgenstein himself is clearly in favor of systematically examining particular cases: “In order to see more clearly, here as in countless similar cases, we must look at what really happens in detail, as it were from close up” (Wittgenstein 2009, 30e). However, once we do abstract away, it is crucial to approach the resulting theory from a pragmatic standpoint: “We want to establish an order in our knowledge of language: an order for a particular purpose, one out of many possible orders, not the order” (Wittgenstein 2009, 56e, original emphasis).

Generative grammar

In many ways, Chomsky conceives of language as the early Wittgenstein did, i.e. under the cathedral metaphor. This may come across as a surprise because unlike Wittgenstein, he is not concerned with issues of meaningfulness, philosophical or otherwise. Indeed, it is one of his fundamental precepts that grammar can and should be dissociated from meaning, as demonstrated by his famous example sentence “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously”, which he claims is perfectly grammatical yet meaningless1 (Chomsky 2002, Chap. 2).

Nevertheless, the goal for both is to describe language per se, in the abstract, without regard to its context-grounded use in actual communication. Both strive to give a highly formal definition of the system they think they are uncovering: while Wittgenstein attempts to establish a logical calculus of how propositions can be said to carry meaning in terms of their referential relationship to external reality, Chomsky tries to hint at a calculus which would determine which candidate sentences belong to the language encoded by this calculus, i.e. separate those that are grammatical from those that are not.

Another way to put this is that the descriptive part of linguistics can be equated with formal language theory: a language is viewed as a (potentially infinite) set of symbol strings (sentences), and the linguist’s task is to find the simplest and most elegant set of rules that would constitute the basis for a procedure to generate (hence generative grammar) all of them and only those, whether observed or potential. Chomsky himself gives the following definition: “by a generative grammar I mean simply a system of rules that in some explicit and well-defined way assigns structural descriptions to sentences” (Chomsky 1965, 8).

Furthermore, “Linguistic theory is concerned primarily with an ideal speaker-listener, in a completely homogeneous speech-community, who knows its language perfectly” (Chomsky 1965, 3). Specifically, it is concerned with his “competence (the speaker-hearer’s [intrinsic] knowledge of his language)”, not his “performance (the actual use of language in concrete situations)” (Chomsky 1965, 4). Additionally, no claim is made as to the cognitive or neurophysiological accuracy of the mechanisms described, although to hedge his bets both ways, Chomsky adds that “No doubt, a reasonable model of language use will incorporate, as a basic component, the generative grammar that expresses the speaker-hearer’s knowledge of the language” (Chomsky 1965, 9).

In short, Chomsky consciously sets up the playing field for a thoroughly mentalistic, speculative discipline. At first, it might seem like reasonable approximation and a small concession to make, especially in the face of the sheer daunting complexity of all the intricate mechanisms that conspire to yield the phenomenon we call language, but only until one fully realizes the consequences of such a move. Observe for instance the carefully crafted loophole claiming that linguistics is primarily concerned with an ideal speaker-hearer’s competence and that actual usage data is just circumstantial evidence. This effectively allows linguists to dismiss inconvenient edge cases or counterexamples to their theories purely on grounds of their being noisy data or slips of the tongue, which is something they are allowed to determine based on introspection. Mind you, this is not just a theoretical loophole; Chomsky himself has repeatedly relied on it, especially with respect to so-called linguistic universals (see e.g. Sampson 2005, 139 or 160).

The net result is rampant, unchecked theorizing. One such example is the postulation of a two-layer linguistic analysis, the observed language data corresponding to a surface structure which provides hints as to an underlying, more regular deep structure to be uncovered. The deep structure is purportedly closer to the universal properties of language; both layers are linked by a system of transformations:

We can greatly simplify the description of English and gain new and important insight into its formal structure if we limit the direct description in terms of phrase structure to a kernel of basic sentences (simple, declarative, active, with no complex verb or noun phrases), deriving all other sentences from these (more properly, from the strings that underlie them) by transformation, possibly repeated. (Chomsky 2002, 106–7)

Constructing a formal framework for grammar modeling with cognitively unmotivated levels of abstraction might have been a valid goal (though arguably not within linguistics) if the result was indeed, as Chomsky claims it to be, maximally elegant, as simple as can be but no simpler. I was not able to track down a formal definition of this criterion, but simplicity is clearly discursively construed as a desirable quality: “simple and revealing” (Chomsky 2002, 11) or “effective and illuminating” (Chomsky 2002, 13) are Chomsky’s choice epithets for what to look for in a grammar. But that is not true either: transformations are an unnecessary addition, singling them out as a separate category of operations adds nothing to the generative power of his system (Pullum 2011, 290). They are therefore a wart under any reasonable definition of “simplicity” and Chomsky thus manages to fall short of even the self-defined, theory-internal standards that are the only ones he allows his enterprise to be held to.

Ontogeny and phylogeny

As we have seen, generative grammar concerns itself with an ideal speaker-hearer’s competence in a perfectly homogeneous community. The trouble is that such an impoverished model eschews any possibility of dynamism. The very dichotomy between grammatical and ungrammatical is intuitively problematic if we consider that judgments are bound to diverge when made in reference to different dialects, sociolects and idiolects,2 not to mention that binary classification might be too reductive in some cases (how would you categorize, on first encounter, a construction which you passively understand but would never produce actively?). Though Chomsky sometimes mentions in passing the possibility of levels of grammaticalness which would allow a finer-grained analysis (e.g. Chomsky 2002, 16; Chomsky 1965, 11), it seems to be just another instance of hedging his bets, he never makes it a fundamental component of his theory. This would seem to indicate that Chomsky’s theory of language has a serious problem in that it is unable to account for any phenomena that involve fluctuations in linguistic ability, including language emergence / diachronic change (phylogeny) and acquisition (ontogeny).

Chomsky’s response to this is that our language faculty is largely innate: we are genetically endowed with a language-acquisition device in our brains (Chomsky 1965, 31–33) which can supposedly infer the correct grammatical rules even given incomplete, limited and noisy input, which is what Chomsky argues children get (the “poverty of stimulus” argument), thanks to strong universal constraints on what a human language can be like. Under this account, the capacity for language, initially “a language of thought, later externalized and used in many ways” (Chomsky 2007, 24), appeared as a random mutation in a single individual and progressively spread through the population because it offered a considerable competitive advantage: “capacities for complex thought, planning, interpretation” (Chomsky 2007, 22).

In his later career, Chomsky increasingly focused on exploring this purported shared genetic basis for human language, hence the aforementioned label “biolinguistics”. Make no mistake, this in no way entails a turn from mentalism towards empirical neurophysiological or genetic investigation. Quite to the contrary, liberated from the constraints of having to account for individual existing languages in detail, he soars to new heights of abstractness in postulating the formal language underpinnings of human language. The principles and parameters model of Universal Grammar (Chomsky 1986) expands upon the notion of linguistic universals by splitting them up into two sets: principles, which are hardwired and immutable, and parameters, which are hardwired too but can be flipped on or off based on linguistic behavior observed by the child in her particular language community. Since the choices are heavily constrained, the learner can infer correct parameter settings in spite of deficient input. This line of research culminates in the so-called minimalist program (Chomsky 1995), where Chomsky identifies the “core principle of language, [the operation of] unbounded Merge” (Chomsky 2007, 22). Under the “strong” minimalist hypothesis, this would be the only principle necessary to account for human-like languages (Chomsky 2007, 20), which would paradoxically essentially discard all work (or should I say speculation?) previously done on the parameters side of the Universal Grammar project. All other universal characteristics of language could then be explained by newly introduced “interface” conditions,3 i.e. constraints on how language inter-operates with other systems, including thought and physical language production (Chomsky 2007, 14);4 all empirically documented variation between the world’s languages would be chalked up to lexical differences (Chomsky 2007, 25).

The poverty of stimulus and language universals arguments for innateness have been thoroughly debunked, especially in Geoffrey Sampson’s book-length diatribe The ‘Language Instinct’ Debate. In short, it turns out that some of the grammatical constructions which were assumed to be absent from a language learner’s input yet acquired nonetheless have since been empirically proven to occur fairly commonly (Sampson 2005, 72–79). Moreover, there is no qualitative difference between a statement like “the stimulus is too poor to allow language learning without a genetic basis” and “the stimulus is just rich enough etc.”, both are unverifiable unless we have already independently proven that language learning occurs one way or the other, so to adduce either of the statements as proof for the hypothesis at stake is misguided (Sampson 2005, 47–48). Finally, the alleged language universals turn out to be either false when checked against additional languages (Sampson 2005, 138–9) or so general as to be meaningless (Sampson 2005, Chap. 5).

Irrespective of this, let us suppose for a moment that genetic mutation and subsequent inheritance do play a role in the emergence of language, and work out an account of language emergence consistent with this hypothesis. If language started out through mutation in a single individual as a purely internal advanced conceptualization faculty, then once it started to spread, what was the motivation for the genetically-endowed humans to externalize their thoughts? How did they know to which of their peers they could speak (which had inherited the mutation) and which not? And most importantly, how did they know which parameters of Universal Grammar to flip on and which off, if there was no prior language based on which to decide? Universal Grammar would have had to be fairly detailed in order for intersubjective agreement on the norms for the first ever human language to be reached on the basis of it alone. Yet as we have seen, Chomsky has been moving away from this notion – at the limit, the minimalist program posits only one very general mechanism required for language. The poverty of stimulus argument is turned against its creator as the argument from poverty of the machinery supposed to make up for the poverty of said stimulus.

Alternatively, if we fully subscribe to the minimalist program and the notion that all the surface variety exhibited by language comes from the lexicon, then how are individual words created, how do they propagate? One might be tempted to say “people just invented them”, but consider for a while that in the current setup, there is absolutely no mechanism that would explain how a community of speakers reaches agreement on their lexicon – this theory offers no incentive whatsoever for consensus to be reached; from its point of view, a solution where each speaker ends up with their own private lexicon is equally valid because indistinguishable on the basis of the theory’s conceptual apparatus. Chomsky’s ideas on phylogenesis appear thoroughly ridiculous when fully carried out to their logical consequences, and this can all be blamed on his sterile, idealized and static view of language which dismisses actual communication as a secondary purpose and therefore a peripheral issue.

On a side note, it is hard to say which aspect of Chomsky’s theory of language came first – whether innateness accommodated the mentalism and the concomitant quest for formal purity (botched as it may be) of generative grammar, whether it was the other way round, or whether they perhaps co-evolved in his mind. The facts are that Chomsky’s initial publications on generative grammar concentrate on the formal language theory part (Chomsky 1956; Chomsky 2002), but he added the innateness argument fairly early on, even tacking a seemingly respectable philosophical lineage onto it in Cartesian Linguistics (Chomsky 2009), which pretends to trace back both innateness and mentalism to Descartes and the Port-Royal grammarians, binding them as two sides of the same coin. It is worth noting that in both formal language theory and history of linguistics / philosophy, Chomsky is more of a dabbler than an expert: he has provably borrowed most of his ideas in the former field from others, sometimes mangling them or extending them in unfortunate ways (Pullum 2011; Sampson 2015), and has thoroughly underresearched (or wilfully twisted?) his understanding of the latter, which has resulted in serious misrepresentations of the history of ideas (Miel 1969; Aarsleff 1970).

Evolutionary linguistics

There are various sub-fields of linguistics which are in discord with generative grammar, especially over the notion that performance data should be used only as evidence for guiding the speculation and detailed usage and frequency patterns should be disregarded; the primacy of syntax (as advocated by Chomsky) is also disputed. One of these sub-fields is obviously corpus linguistics, which takes a decidedly empiricist stance and starts by assembling a large body of language data (a corpus) from which patterns of language use are inferred. Nevertheless, not all of these compete with generative grammar at the fundamental explanatory level of how language came about phylogenetically and how it is transmitted by ontogenetic acquisition.

We have repeatedly encountered Chomsky’s emphasis on how communication, actual interactions between speakers, are just an afterthought in the system of language:

evolutionary biologist Salvador Luria was the most forceful advocate of the view that communicative needs would not have provided “any great selective pressure to produce a system such as language,” with its crucial relation to “development of abstract or productive thinking.” His fellow Nobel laureate François Jacob (1977) added later that “the role of language as a communication system between individuals would have come about only secondarily, as many linguists believe,” (Chomsky 2007, 23)

Part of this vehemence dovetails with the single individual mutation hypothesis of the origins of language – it helps if the significance of communication is downplayed in an account where communication is initially impossible, simply because there is no other language-endowed being to communicate with. If communication were language’s killer feature, then the selective pressure for the incriminated gene to propagate would not kick in.

The other part can reasonably be attributed to Chomsky’s intent to make a clean break from a prior popular theory on language acquisition, epitomized by B. F. Skinner’s 1957 monograph Verbal Behavior, which offered a heavily empiricist, behaviorist account of language learning in terms of a stimulus-response cycle. Characteristically, Chomsky’s strategy is to trivialize the function of the stimulus, casually implying both that it might not be needed at all, and if it is, then details of the role it plays are of little interest:

it would not be at all surprising to find that normal language learning requires use of language in real-life situations, in some way. But this, if true [sic!], would not be sufficient to show that information regarding situational context (in particular, a pairing of signals with structural descriptions that is at least in part prior to assumptions about syntactic structure) plays any role in determining how language is acquired, once the mechanism is put to work and the task of language learning is undertaken by the child. (Chomsky 1965, 33)

In retrospect, Skinner’s account may be simplistic in many ways, but the basic notion that one has to pay attention to stimuli and responses in the course of particular linguistic interactions is sound. In particular, a theory of language built on this foundation successfully copes with all of the impasses we have explored above regarding Chomsky’s approach. One such framework is that of evolutionary linguistics.

Evolutionary linguistics views language as a complex adaptive system with emergent properties (Steels 2015, 8–9). A complex adaptive system is a system which is not centrally organized, coordinated or designed: its “macroscopic” characteristics are said to “emerge” as the result of localized interactions between individual entities (agents) with similar “microscopic” characteristics (be they physical, behavioral or motivational). The whole is more than the sum of its parts, and none of the agents can be properly said to have designed the system, nor can they deliberately change it in an arbitrary way; but all are continuously shaping it by taking part in the interactions that constitute its fabric. Examples of complex adaptive systems include the dynamics of insect societies (beehives, ant nests) or patterns of collective motion in large animal groups (flocks of birds or shoals of fish). These and more are discussed in much greater depth in the first chapter of Pierre-Yves Oudeyer’s book Self-Organization in the Evolution of Speech. Adaptiveness is a property that these systems acquire by virtue of not being hardwired on the macro level: they are defined functionally instead of structurally. If the conditions in the environment change, the system will adapt to keep fulfilling its function, because the agents are forced to modify their behavior in order to achieve their individual goals. Of course, they may fail to do so, in which case the system breaks down and ceases to exist.

If we revert to the metaphor from the title of the present essay, according to Chomsky, language is a cathedral erected by a single unwitting architect, the random genetic mutation that endowed us with the language faculty. Conversely, Luc Steels and fellow evolutionary linguists argue that the apparent macroscopic orderliness of language is the result of a myriad interactions of multiple individual agents, as suggested by the the bazaar image.

One form that linguistic research can take under this paradigm is formulating and running computational models which simulate the behavior of agent populations and study the microscopic conditions, i.e. the cognitive and physical abilities, motivations etc. of each agent, necessary for a system like language to emerge within the population and stabilize. By direct inspiration from Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, the interactions between agents are termed “language games” (Steels 2015, 167–8); depending on the topic being investigated, the agents can play different types of language games with different rules. It is openly acknowledged that such simulations represent only a limited approximation of a well-defined subspace of the actual uses of language. In the research to date, rules are generally definite and set for the entire experiment, but simulating language games with fuzzy rules remains a perfectly valid research topic within this framework, in the Wittgensteinian spirit of allowing rules to be made up and modified “as we go along” (Wittgenstein 2009, 44e).

A relatively simple game that agents can play is the so-called Guessing Game (see Chap. 2 of Steels 2015 for more details). In this scenario, a population of agents, embodied in physical robots, tries to establish a shared lexicon and coupled ontology for a simple world consisting of geometrical shapes. Each game is an interaction of two agents picked at random, in the context of a scene consisting of said geometrical shapes. One agent (the speaker) takes the initiative, selects a topic from the scene and names it; the other (the hearer) tries to guess which object the first one had in mind and points to it; the speaker decodes the pointing gesture and the game succeeds if he interprets it as referencing his original topic. If so, he acknowledges the match; otherwise, he points at the intended topic as a repair strategy. At the outset, neither the lexicon nor the ontology are given, only a set of sensors and actuators (which allow the agents to interact with the environment by taking in streams of raw perceptual data or producing sound and pointing gestures) and very general cognitive principles. These include an associative memory and feedback mechanisms to propagate failures and successes in conceptualization and communication to all components of the system and act on them.5 New distinctions along the perceptual dimensions are introduced in a random fashion,6 but those that lead to a successful unambiguous selection of a topic and communicative success are strengthened over the course of many interactions, while useless ones are dampened by lateral inhibition and eventually pruned. At the same time, speakers create new words for concepts that are as of yet missing from their lexicon, and hearers may adopt them into theirs for their conceptualization of the topic the speaker points at in case of failure. A similar feedback mechanism then ensures that highly successful words are preferred and come to dominate within the speech community. It is important to realize that at no time do the individual agents share the same ontology or lexicon: newly introduced distinctions and words are random and unique for each agent, agents simply gradually learn which of these are useful in achieving communicative success, which means that they naturally settle on ontologies and lexicons that are close enough to those of others in the population.

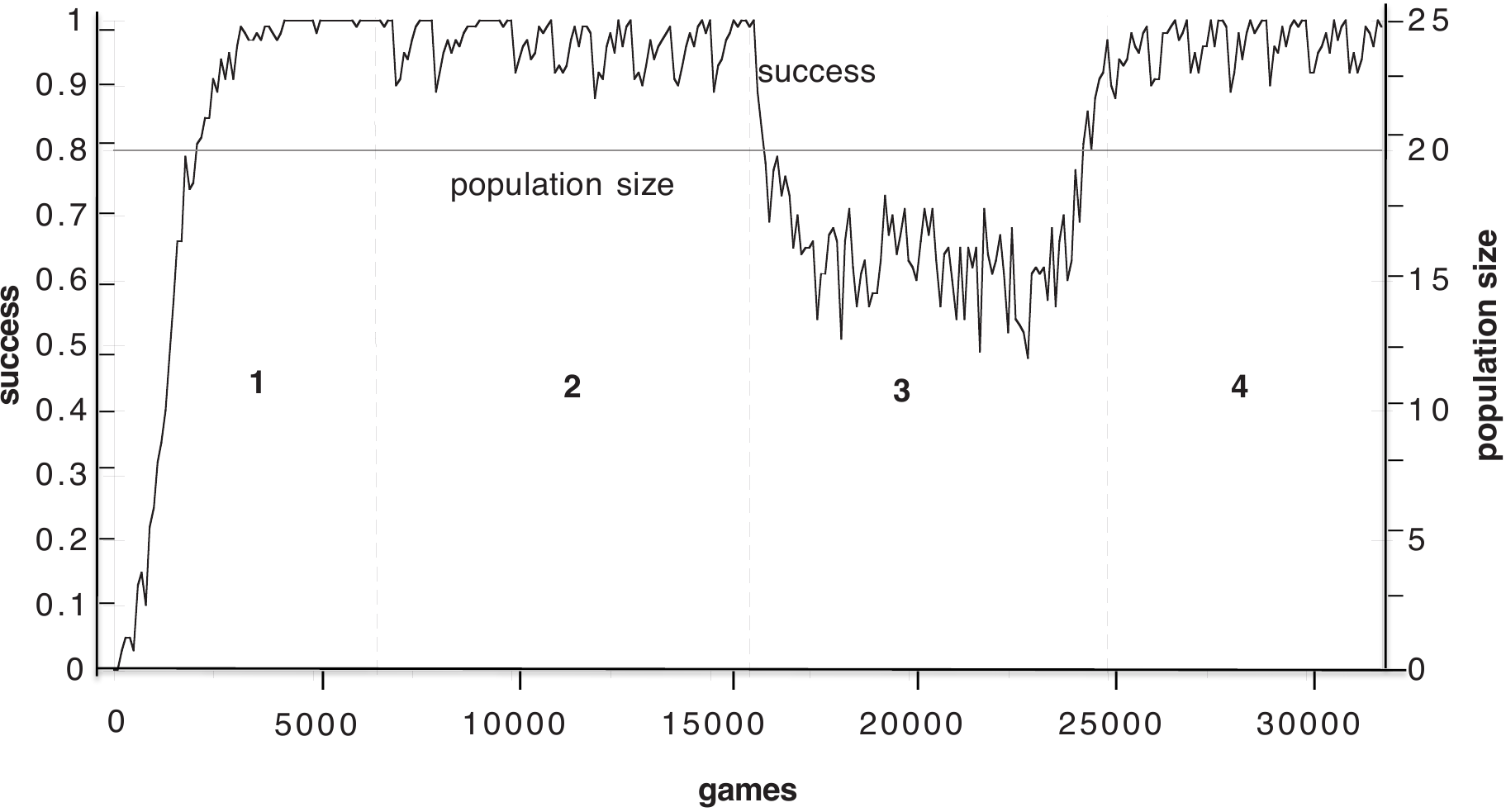

This barely scratches the surface of how all these notions must be orchestrated for a working computer implementation of this model, not to mention the even more elaborate agent-based language game modeling experiments that are already being conducted, investigating for instance the emergence of grammar (see Part III of Steels 2015 for an overview of recent scholarship). We see that even a seemingly simple task like establishing a shared conceptualization of reality and agreeing on names for these concepts is a complex endeavor which relies on a highly sophisticated (though also highly general) machinery. Another key observation is that while agent-based models can be fully virtual, grounding them in physical reality (cf. the use of robots with sensors and actuators) brings additional challenges that enable researchers to reach vital insights which would otherwise be impossible. In particular, grounding introduces fuzziness on the sensory input channels (by virtue of different points of view for the two robots and analog-to-digital conversion) which the agents must cope with, or else the mechanisms they were endowed with cannot be considered as constituting a plausible, sufficient model of the dynamics of human language. Unlike in generative grammar, anything that is transient, imperfect, is eminently included in the purview of linguistic inquiry. Failures are very much part of the dynamics that steer the evolution of language. How could it adapt to the speakers’ changing requirements if it did not include appropriate repair strategies? Indeed, how could it be bootstrapped at all? The reward is a model that successfully simulates not only language emergence, but also transmission: if virgin agents are added into an existing population, they gradually acquire its language (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Communicative success in a population of agents with a steady influx of virgin agents and outflux of old ones (overall population size remains the same). The game starts in phase 1 with 20 virgin agents; phases 2 and 4 show the behavior of the model at an agent renewal rate of 1/1000 games, whereas phase 3 corresponds to a heavier rate of 1/100. (Figure from Steels 2015, 121.)

Crucially, the drive to communicate, to interact, is built into the agents, they just keep playing games as long as they can. But if it was not, the simulation would have to be more complex and somehow elicit this drive by introducing appropriate ecological constraints, e.g. by requiring co-operation as a survival strategy (Steels 2015, 106). Otherwise, the agents would have no motivation to strive for communicative success in their mutual encounters, they would fail to reach intersubjective alignment of their conceptual spaces and lexicons, and language would not emerge. In other words, far from being an afterthought, successful communication with a partner, grounded in an external context, turns out to be a fundamental requirement to establish the kind of dynamics which allow languages to appear.

Paradoxically, since it concerns itself with simulations and computational models, this branch of evolutionary linguistics is, like generative grammar, also highly speculative. However, unlike generative grammar, it is a kind of speculation which considers guidance by empirical observations a necessity, not a nuisance. Furthermore, simulations are meant to be tested: if an agent-based model of language emergence fails to converge on the result stipulated for that particular experiment, the model is plain wrong and the dynamics it is trying to put into place (cognitive strategies, feedback propagation etc.) need to be revised. There is thus a clear-cut criterion for validity. Lastly, even if a simulation works, an accompanying debate as to whether the mechanisms involved are actually plausible approximations of reality is considered an integral part of hypothesis evaluation, with evidence from strongly empirically grounded disciplines like biology and neurophysiology a vital element in the process.

Conclusion

Taking a cue from Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, this essay should not be construed as an attempt to replace one doctrine with another, but to advocate a “change of attitude” (cf. McGinn 2013, 33) which allows asking more meaningful questions about language. This being said, on the evidence presented above, it is hard not to conclude that Noam Chomsky is fundamentally mistaken about the corrective that is necessary for language learning to take place. According to Chomsky, the criterion for evaluating linguistic rules lies within a dedicated language organ we are genetically endowed with; the innate structures themselves embody the metric by which conjectures pertaining to linguistic rules will be judged. By contrast, in the evolutionary linguistics perspective, genetics provide innate structures which are capable of random growth, but the feedback (reinforcement and pruning) which results in steering this growth in a particular direction comes from interactions with the environment. This theory presupposes much less specificity in the hardware infrastructure which makes this possible and so should be preferred both on grounds of simplicity and flexibility of the model, not to mention that it is biologically plausible and has been empirically verified to work.

In the context of science, Chomsky’s rhetorical strategy in and of itself is dishonest: he preaches formal rigor while practicing sleight of hand, and casually retreats to increasingly abstract ground on reaching an impasse. He thus carves out a region in discursive space which has no corresponding equivalent in a logically consistent conceptual space, without which a piece of discourse can hardly constitute a scientific theory. In other words, much like his famous example sentence “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously”, his discourse is grammatical but largely nonsensical under the requirements on a system of thought which aspires to mirror reality in a coherent fashion.

Requirements on scientific discourse notwithstanding, we as linguists should keep in mind that language in general is much more than a system for encoding logical propositions. Even Wittgenstein had to resign himself to the fact – or perhaps knew all along – that the Tractatus, which he framed as the ultimate solution to all metaphysical controversies, could only fan the flames of philosophical debate. It was after all addressed to a diverse community of people bound perhaps exclusively by their penchant for elaborate language games.

References

Aarsleff, Hans. 1970. “The History of Linguistics and Professor Chomsky.” Language 46 (3): 570–85.

Chomsky, Noam. 1956. “Three Models for the Description of Language.”

———. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press.

———. 1986. Knowledge of Language: Its Nature, Origin, and Use. Convergence. New York, Westport, London: Praeger.

———. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

———. 2002. Syntactic Structures. 2nd ed. Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

———. 2007. “Of Minds and Language.” Biolinguistics, no. 1: 9–27.

———. 2009. Cartesian Linguistics: A Chapter in the History of Rationalist Thought. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McGinn, Marie. 2006. Elucidating the Tractatus: Wittgenstein’s Early Philosophy of Logic and Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 2013. The Routledge Guidebook to Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. The Routledge Guides to Great Books. Routledge.

Miel, Jan. 1969. “Pascal, Port-Royal, and Cartesian Linguistics.” Journal of the History of Ideas 30 (2): 261–71.

Oudeyer, Pierre-Yves. 2006. Self-Organization in the Evolution of Speech. Translated by James R. Hurford. Oxford, New York: OUP.

Pullum, Geoffrey K. 2011. “On the Mathematical Foundations of Syntactic Structures.” Journal of Logic, Language and Information 20: 277–96.

Raymond, Eric S. 1999. The Cathedral & the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary. O’Reilly Media.

Sampson, Geoffrey. 2005. The “Language Instinct” Debate. 3rd ed. London, New York: Continuum.

———. 2015. “Rigid Strings and Flaky Snowflakes.” Language and Cognition 10: 1–17.

Skinner, B. F. 1957. Verbal Behavior. The Century Psychology Series. New York: Appleton – Century – Crofts.

Steels, Luc. 2015. The Talking Heads Experiment: Origins of Words and Meanings. Computational Models of Language Evolution 1. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 2001. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Routledge Classics. London, New York: Routledge.

———. 2009. Philosophical Investigations. Chichester, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing.

-

Let us pretend for a moment that language games like “poetry” or the surrealist pastime of cadavre exquis do not exist; in these, the quoted sentence could appear as perfectly valid and meaningful, though perhaps not in the sense that Chomsky intended. “Meaningful” in a late-Wittgensteinian perspective could be paraphrased as “accepted by at least one involved party as a valid turn within the context of a particular language game”. ↩

-

Arguing that this does not matter because we should be concerned with the ideal speaker-hearer’s competence just takes us further down the impasse, because now we have to determine how to delimit the purported “ideal”. ↩

-

This is the beauty of building empirically unmotivated, purely speculative theories: at any moment, one can freely accommodate a new element into the existing framework, substituting novelty and amalgamation for critical evaluation. ↩

-

Cf. also Sampson’s riposte : “If complex properties of some aspect of human behaviour have to be as they are as a matter of conceptual necessity, then there is no reason to postulate complex genetically inherited cognitive machinery determining those behaviour patterns” (Sampson 2015, 9). ↩

-

This interconnected architecture stands in stark contrast to Chomsky’s deliberately isolationist approach: “the relation between semantics and syntax […] can only be studied after the syntactic structure has been determined on independent grounds” (Chomsky 2002, 17). ↩

-

Wittgenstein only hints at the problem of conceptualization, but he is prescient in realizing it is not a given: “The primary elements [of the objects which constitute the world in this particular language game] are the coloured squares. ‘But are these simple?’ – I wouldn’t know what I could more naturally call a ‘simple’ in this language-game. But under other circumstances, I’d call a monochrome square, consisting perhaps of two rectangles or of the elements colour and shape, ‘composite’” (Wittgenstein 2009, 27e). ↩

Comments

comments powered by Disqus