Note: This text uses the Python programming language to give some hands-on experience of the concepts discussed. If you're not familiar with programming at all, much less with Python, my advice is:

- either: ignore the code, focus on the comments around it, they should be enough to follow the thread of the explanation;

- or, if you've got a little more time: Python is pretty intuitive, so you might want to have a look at the code examples anyway.

In any case, the code might make more sense to you if you tinker with it in an interactive Python session:

And now, without further ado...

Much like any other piece of data inside a digital computer, text is represented as a series of binary digits (bits), i.e. 0's and 1's. A mapping between sequences of bits and characters is called an encoding. How many different characters your encoding can handle depends on how many bits you allow per character:

- with 1 bit you can have 2^1 = 2 characters (one is mapped to 0, the other to 1)

- with 2 bits you can have 2^2 = 2*2 = 4 characters (mapped to 00, 01, 10 and 11)

- with 3 bits you can have 2^3 = 2*2*2 = 8 characters

- etc.

Now, a short digression on representing numbers, to make sure we're all on the same page: in the context of computers, you often see the same number represented in three different ways:

- as a decimal number, using 10 digits 0--9 (e.g. 12)

- as a binary number, using only 2 digits, 0 and 1 (e.g. 1100, which equals decimal 12)

- as a hexadecimal number, using 16 digits: 0--9 and a--f (e.g. c, which also equals decimal 12)

As a consequence, the need often arises to convert between these different numeral systems. If you don't want to do so by hand, Python has your back! The bin() function gives you a string representation of the binary form of a number:

bin(65)

As you can see, in Python, binary numbers are given a 0b prefix to distinguish them from regular (decimal) numbers. The number itself is what follows after (i.e. 1000001).

Similarly, hexadecimal numbers are given an 0x prefix:

hex(65)

To convert in the opposite direction, i.e. to decimal, just evaluate the binary or hexadecimal representation of a number:

0b1000001

0x41

Numbers using these different bases (base 2 = binary, base 10 = decimal, base 16 = hexadecimal) are mutually compatible, e.g. for comparison purposes:

0b1000001 == 0x41 == 65

Why are hexadecimals useful? They're primarily a more convenient, condensed way of representing sequences of bits: each hexadecimal digit can represent 16 different values, and therefore it can stand in for a sequence of 4 bits (2^4 = 16).

0xa == 0b1010

0xb == 0b1011

# if we paste together hexadecimal a and b, it's the

# same as pasting together binary 1010 and 1011

0xab == 0b10101011

In other words, instead of binary 10101011, we can just write hexadecimal ab and save ourselves some space. Of course, this only works if shorter binary numbers are padded to a 4-bit width:

0x2 == 0b10

0x3 == 0b11

# if we paste together hexadecimal 2 and 3, we have to

# paste together binary 0010 and 0011...

0x23 == 0b00100011

# ... not just 10 and 11

0x23 == 0b1011

The padding has no effect on the value, much like decimal 42 and 00000042 are effectively the same numbers.

Now back to text encodings. The oldest encoding still in widespread use is ASCII, which is a 7-bit encoding. What's the number of different sequences of seven 1's and 0's?

# this is how Python spells 2^7, i.e. 2*2*2*2*2*2*2

2**7

This means ASCII can represent 128 different characters, which comfortably fits the basic Latin alphabet (both lowercase and uppercase), Arabic numerals, punctuation and some "control characters" which were primarily useful on the old teletype terminals for which ASCII was designed. For instance, the letter "A" corresponds to the number 65 (1000001 in binary, see above).

"ASCII" stands for "American Standard Code for Information Interchange" -- which explains why there are no accented characters, for instance.

Nowadays, ASCII is represented using 8 bits (= 1 byte), because that's the unit of computer memory which has become ubiquitous (in terms of both hardware and software assumptions), but still uses only 7 bits' worth of information. That extra bit means that there's room for another 128 characters in addition to the 128 ASCII ones, coming up to a total of 256.

2**(7+1)

What happens in the range [128; 256) is not covered by the ASCII standard. In the 1990s, many encodings were standardized which used this range for their own purposes, usually representing additional accented characters used in a particular region. E.g. Czech (and Slovak, Polish...) alphabets can be represented using the ISO latin-2 encoding, or Microsoft's cp-1250. Encodings which stick to the same character mappings as ASCII in the range [0; 128) and represent them physically in the same way (as 1 byte), while potentially adding more character mappings beyond that, are called ASCII-compatible.

ASCII compatibility is a good thing™, because when you start reading a character stream in a computer, there's no way to know in advance what encoding it is in (unless it's a file you've encoded yourself). So in practice, a heuristic has been established to start reading the stream assuming it is ASCII by default, and switch to a different encoding if evidence becomes available that motivates it. For instance, HTML files should all start something like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8"/>

...

This way, whenever a program wants to read a file like this, it can start off with ASCII, waiting to see if it reaches the charset (i.e. encoding) attribute, and once it does, it can switch from ASCII to that encoding (UTF-8 here) and restart reading the file, now fairly sure that it's using the correct encoding. This trick works only if we can assume that whatever encoding the rest of the file is in, the first few lines can be considered as ASCII for all practical intents and purposes.

Without the charset attribute, the only way to know if the encoding is right would be for you to look at the rendered text and see if it makes sense; if it did not, you'd have to resort to trial and error, manually switching the encodings and looking for the one in which the numbers behind the characters stop coming out as gibberish and are actually translated into intelligible text.

Let's take a look at printable characters in the Latin-2 character set. The character set consists of mappings between positive integers (whole numbers) and characters; each one of these is called a codepoint. The Latin-2 encoding then defines how to encode each of these integers as a series of bits (1's and 0's) in the computer's memory.

latin2_printable_characters = []

# the Latin-2 character set has 256 codepoints, corresponding to

# integers from 0 to 255

for codepoint in range(256):

# the Latin-2 encoding is simple: each codepoint is encoded

# as the byte corresponding to that integer in binary

byte = bytes([codepoint])

character = byte.decode(encoding="latin2")

if character.isprintable():

latin2_printable_characters.append((codepoint, character))

latin2_printable_characters

Using the 8th bit (and thus the codepoint range [128; 256)) solves the problem of handling languages with character sets different than that of American English, but introduces a lot of complexity -- whenever you come across a text file with an unknown encoding, it might be in one of literally dozens of encodings. Additional drawbacks include:

- how to handle multilingual text with characters from many different alphabets, which are not part of the same 8-bit encoding?

- how to handle writing systems which have way more than 256 "characters", e.g. Chinese, Japanese and Korean (CJK) ideograms?

For these purposes, a standard character set known as Unicode was developed which strives for universal coverage of (ultimately) all characters ever used in the history of writing, even adding new ones like emojis. Unicode is much bigger than the character sets we've seen so far -- its most frequently used subset, the Basic Multilingual Plane, has 2^16 codepoints, but overall the number of codepoints is past 1M and there's room to accommodate many more.

2**16

Now, the most straightforward representation for 2^16 codepoints is what? Well, it's simply using 16 bits per character, i.e. 2 bytes. That encoding exists, it's called UTF-16 ("UTF" stands for "Unicode Transformation Format"), but consider the drawbacks:

- we've lost

ASCIIcompatibility by the simple fact of using 2 bytes per character instead of 1 (encoding "a" as01100001or00000000|01100001, with the|indicating an imaginary boundary between bytes, is not the same thing) - encoding a string in a language which is mostly written down using basic letters of the Latin alphabet now takes up twice as much space (which is probably not a good idea, given the general dominance of English in electronic communication)

Looks like we'll have to think outside the box. The box in question here is called fixed-width encodings -- all of the encoding schemes we've encountered so far were fixed-width, meaning that each character was represented by either 7, 8 or 16 bits. In other word, you could jump around the string in multiples of 7, 8 or 16 and always land at the beginning of a character. (Not exactly true for UTF-16, because it is something more than just a "16-bit ASCII": it has ways of handling characters beyond 2^16 using so-called surrogate sequences -- but you get the gist.)

The smart idea that some bright people have come up with was to use a variable-width encoding. The most ubiquitous one currently is UTF-8, which we've already met in the HTML example above. UTF-8 is ASCII-compatible, i.e. the 1's and 0's used to encode text containing only ASCII characters are the same regardless of whether you use ASCII or UTF-8: it's a sequence of 8-bit bytes. But UTF-8 can also handle many more additional characters, as defined by the Unicode standard, by using progressively longer and longer sequences of bits.

def print_utf8_bytes(char):

"""Prints binary representation of character as encoded by UTF-8.

"""

# encode the string as UTF-8 and iterate over the bytes;

# iterating over a sequence of bytes yields integers in the

# range [0; 256); the formatting directive "{:08b}" does two

# things:

# - "b" prints the integer in its binary representation

# - "08" left-pads the binary representation with 0's to a total

# width of 8, which is the width of a byte

binary_bytes = [f"{byte:08b}" for byte in char.encode("utf8")]

print(f"{char!r} encoded in UTF-8 is: {binary_bytes}")

print_utf8_bytes("A") # the representations...

print_utf8_bytes("č") # ... keep...

print_utf8_bytes("字") # ... getting longer.

How does that even work? The obvious problem here is that with a fixed-width encoding, you just chop up the string at regular intervals (7, 8, 16 bits) and you know that each interval represents one character. So how do you know where to chop up a variable width-encoded string, if each character can take up a different number of bits?

Essentially, the trick is to use some of the bits in the representation of a codepoint to store information not about which character it is (whether it's an "A" or a "字"), but how many bits it occupies. In other words, if you want to skip ahead 10 characters in a string encoded with a variable width-encoding, you can't just skip 10 * 7 or 8 or 16 bits; you have to read all the intervening characters to figure out how much space they take up. Take the following example:

for char in "Básník 李白":

print_utf8_bytes(char)

Notice the initial bits in each byte of a character follow a pattern depending on how many bytes in total that character has:

- if it's a 1-byte character, that byte starts with 0

- if it's a 2-byte character, the first byte starts with 11 and the following one with 10

- if it's a 3-byte character, the first byte starts with 111 and the following ones with 10

This makes it possible to find out which bytes belong to which characters, and also to spot invalid strings, as the leading byte in a multi-byte sequence always "announces" how many continuation bytes (= starting with 10) should follow.

So much for a quick introduction to UTF-8 (= the encoding), but there's much more to Unicode (= the character set). While UTF-8 defines only how integer numbers corresponding to codepoints are to be represented as 1's and 0's in a computer's memory, Unicode specifies how those numbers are to be interpreted as characters, what their properties and mutual relationships are, what conversions (i.e. mappings between (sequences of) codepoints) they can undergo, etc.

Consider for instance the various ways diacritics are handled: "č" can be represented either as a single codepoint (LATIN SMALL LETTER C WITH CARON -- all Unicode codepoints have cute names like this) or a sequence of two codepoints, the character "c" and a combining diacritic mark (COMBINING CARON). You can search for the codepoints corresponding to Unicode characters e.g. here and play with them in Python using the chr(0xXXXX) built-in function or with the special string escape sequence \uXXXX (where XXXX is the hexadecimal representation of the codepoint) -- both are ways to get the character corresponding to the given codepoint:

# "č" as LATIN SMALL LETTER C WITH CARON, codepoint 010d

print(chr(0x010d))

print("\u010d")

# "č" as a sequence of LATIN SMALL LETTER C, codepoint 0063, and

# COMBINING CARON, codepoint 030c

print(chr(0x0063) + chr(0x030c))

print("\u0063\u030c")

# of course, chr() also works with decimal numbers

chr(269)

This means you have to be careful when working with languages that use accents, because to a computer, the two possible representations are of course different strings, even though to you, they're conceptually the same:

s1 = "\u010d"

s2 = "\u0063\u030c"

# s1 and s2 look the same to the naked eye...

print(s1, s2)

# ... but they're not

s1 == s2

Watch out, they even have different lengths! This might come to bite you if you're trying to compute the length of a word in letters.

print("s1 is", len(s1), "character(s) long.")

print("s2 is", len(s2), "character(s) long.")

For this reason, even though we've been informally calling these Unicode entities "characters", it is more accurate and less confusing to use the technical term "codepoints".

Generally, most text out there will use the first, single-codepoint approach whenever possible, and pre-packaged linguistic corpora will try to be consistent about this (unless they come from the web, which always warrants being suspicious and defensive about your material). If you're worried about inconsistencies in your data, you can perform a normalization:

from unicodedata import normalize

# NFC stands for Normal Form C; this normalization applies a canonical

# decomposition (into a multi-codepoint representation) followed by a

# canonical composition (into a single-codepoint representation)

s1 = normalize("NFC", s1)

s2 = normalize("NFC", s2)

s1 == s2

Let's wrap things up by saying that Python itself uses Unicode internally, but the encoding it defaults to when opening an external file depends on the locale of the system (broadly speaking, the set of region, language and character-encoding related settings of the operating system). On most modern Linux and macOS systems, this will probably be a UTF-8 locale and Python will therefore assume UTF-8 as the encoding by default. Unfortunately, Windows is different. To be on the safe side, whenever opening files in Python, you can specify the encoding explicitly:

with open("unicode.ipynb", encoding="utf-8") as file:

pass

In fact, it's always a good idea to specify the encoding explicitly, using UTF-8 as a default if you don't know, for at least two reasons -- it makes your code more:

- portable -- it will work the same across different operating systems which assume different default encodings;

- and resistant to data corruption --

UTF-8is more restrictive than fixed-width encodings, in the sense that not all sequences of bytes are validUTF-8. E.g. if one byte starts with 11, then the following one must start with 10 (see above). If it starts with anything else, it's an error. By contrast, in a fixed-width encoding, any sequence of bytes is valid. Decoding will always succeed, but if you use the wrong fixed-width encoding, the result will be garbage, which you might not notice. Therefore, it makes sense to default toUTF-8: if it works, then there's a good chance that the file actually was encoded inUTF-8and you've read the data in correctly; if it fails, you get an explicit error which prompts you to investigate further.

Another good idea, when dealing with Unicode text from an unknown and unreliable source, is to look at the set of codepoints contained in it and eliminate or replace those that look suspicious. Here's a function to help with that:

import unicodedata as ud

from collections import Counter

import pandas as pd

def inspect_codepoints(string):

"""Create a frequency distribution of the codepoints in a string.

"""

char_frequencies = Counter(string)

df = pd.DataFrame.from_records(

(

freq,

char,

f"U+{ord(char):04x}",

ud.name(char),

ud.category(char)

)

for char, freq in char_frequencies.most_common()

)

df.columns = ("freq", "char", "codepoint", "name", "category")

return df

Depending on your font configuration, it may be very hard to spot the two intruders in the sentence below. The frequency table shows the string contains regular LATIN SMALL LETTER T and LATIN SMALL LETTER G, but also their specialized but visually similar variants MATHEMATICAL SANS-SERIF SMALL T and LATIN SMALL LETTER SCRIPT G. You might want to replace such codepoints before doing further text processing...

inspect_codepoints("Intruders here, good 𝗍hinɡ I checked.")

... because of course, for a computer, the word "thing" written with two different variants of "g" is really just two different words, which is probably not what you want:

"thing" == "thinɡ"

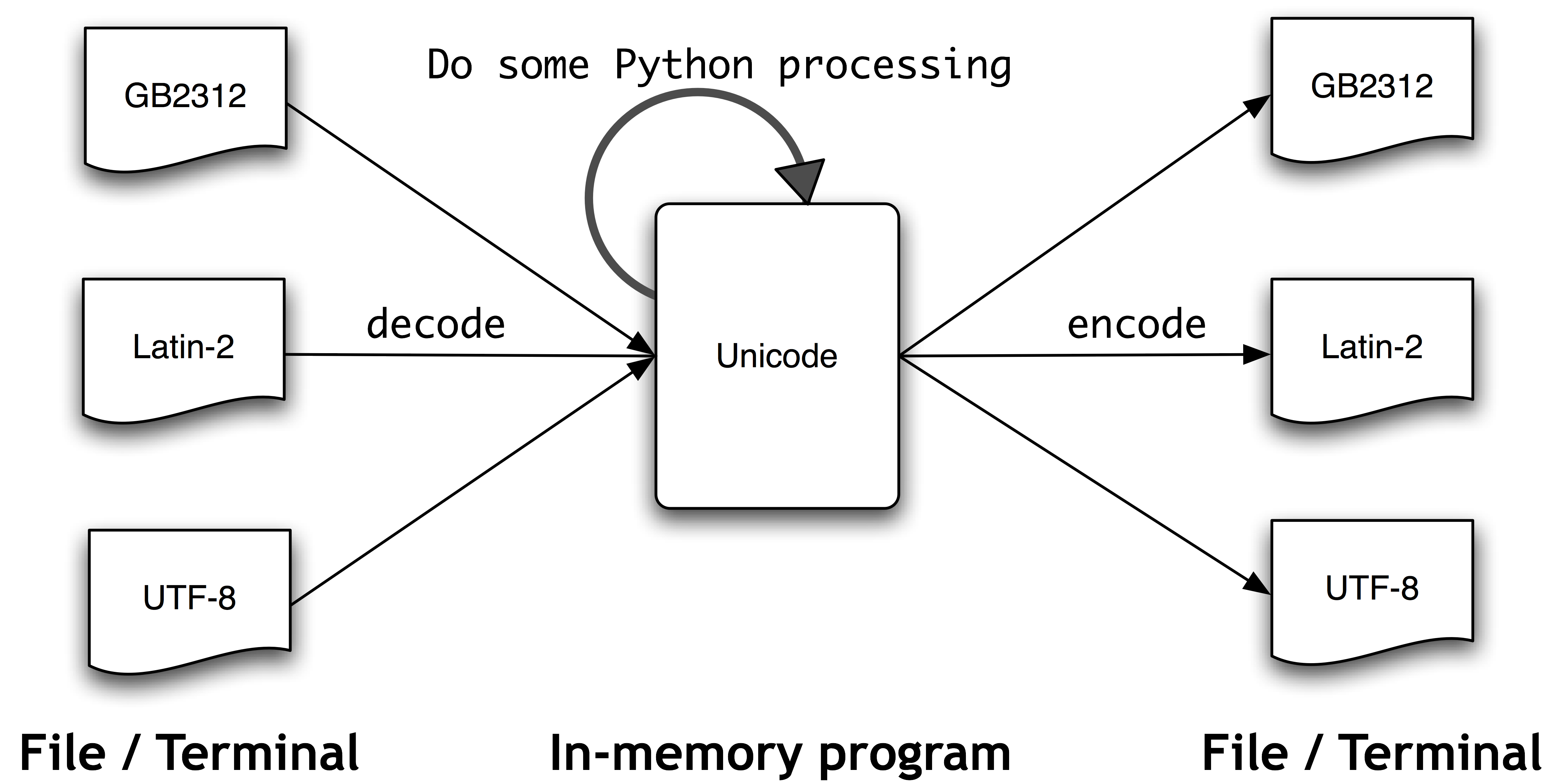

Finally, to put things into perspective, here's a diagram what happens when processing text with Python ("Unicode" in the central box stands for Python's internal representation of Unicode, which is not UTF-8 nor UTF-16):

(Image shamelessly hotlinked from / courtesy of the NLTK Book. Go check it out, it's an awesome intro to Python programming for linguists!)

A terminological postscript: we've been using some terms a bit informally, but now that we have a practical intuition for what they mean, it's good to get the definitions straight in one's head. So, a character set is a mapping between codepoints (integers) and characters. We may for instance say that in our character set, the integer 99 corresponds to the character "c".

On the other hand, an encoding is a mapping between a codepoint (an integer) and a physical sequence of 1's and 0's that represent it in memory. With fixed-width encodings, this mapping is generally straightforward -- the 1's and 0's directly represent the given integer, only in binary and padded with zeros to fit the desired width. With variable-width encodings, which have to explicitly encode information about how many bits are spanned by each codepoint, this straightforward correspondence breaks down.

A comparison might be helpful here: as encodings,

UTF-8andUTF-16both use the same character set -- the same integers corresponding to the same characters. But since they're different encodings, when the time comes to turn these integers into sequences of bits to store in a computer's memory, each of them generates a different one.

For more on Unicode, a great read already hinted at above is Joel Spolsky's The Absolute Minimum Every Software Developer Absolutely, Positively Must Know About Unicode and Character Sets (No Excuses!). Another great piece of material is the Characters, Symbols and the Unicode Miracle video by the Computerphile channel on YouTube. To make the discussion digestible for newcomers, I sometimes slightly distorted facts about how things are "really really" done. And some inaccuracies may be genuine mistakes. In any case, please let me know in the comments! I'm grateful for feedback and looking to improve this material; I'll fix the mistakes and consider ditching some of the simplifications if they prove untenable :)

Comments

comments powered by Disqus